My last

Reading Roll was back in March last year but, the thing is... I never stopped reading! I just stopped posting reviews because I switched to reading the texts on the

new HSC NSW English Prescriptions List, and have been talking about them in the context of their appropriateness to the new English syllabuses

here,

here,

here,

here and

here. Every now and again I make a little time to read some non-Prescribed texts and below are some of these non-Prescriptions, most of which were graphic novels. Some of these I read just for fun but would still be good for classroom use.

Hanawalt is probably best known for her work on the TV series Bojack Horseman. This graphic novel is less a novel and more a collection of comic vignettes exploring absurdist tangents and autobiographical snippets of Hanawalt's life (mostly in regards to food). The author's hilariously askew sense-of-humour had me laughing out-loud a lot, and it took me absolutely no time at all to read from cover to cover.

The Imposter's Daughter by Laurie Sandell

Joining the hallowed annals of graphic novel memoirs is no mean feat but I would easily put Sandell's story alongside other personal accounts such as Craig Thompson's Blankets and Alison Bechdel's Fun Home. Sandell is probably best known for her work as a journalist and editor for magazines such as Glamour, Marie Claire, Esquire, GQ, etc., however, in this frank and sometimes unbelievable memoir she weaves together an arresting narrative of finding her feet in writing and gradually discovering her father's uncanny (and highly damaging) gift for con-artistry.

Big History by DK

Have you ever looked at the subject of history and wondered, "Where's all the stuff that happened before humans came along?" Well, if so, then Big History is the coffee table book for you. This vibrant, illustrated DK guide to David Christian's groundbreaking combination of history and science helps to make clear the recurring patterns that unify all of history as we know it. A hugely informative book.

Wilson by Daniel Clowes

This graphic novel is a disarmingly brisk jaunt through the life of the titular misanthrope, a curmudgeonly loner who insists on voicing his criticisms in just about every situation. What's perhaps most interesting about Wilson is its structure, with Clowes depicting his protagonist's life in a serialised form over the course of single-page strips (like the sort of comic strips you'd see in newspapers) despite the whole thing having been constructed as a graphic novel. This means that we get these snapshots of Wilson's life, condensing a much larger narrative into 70 single strips that each end in a twisted take on the stereotypical gags associated with Sunday morning newspaper cartoons.

Night Air and Volcano Trash by Ben Sears

My only criticism of Sears' fantasy/sci-fi series is that each volume flies by so quickly that you're left wishing you didn't have to wait so long until the next installment of Plus Man's exhilarating adventures with his robotic sidekick Hank. Think Adventure Time mixed with the buoyant, minimalist artwork of Tintin. Great for all ages!

Last Look by Charles Burns

Charles Burns is probably best known for his creepy, psychedelic graphic novel Black Hole. The volume Last Look brings together his most recent trilogy of graphic novels, and complexly weaves together two narratives that dance around themes of psychosis, anxiety, and guilt. Burns is a master of symbolism and the bizarrely disturbing, and all I'll say is that if you read this you'll need to commit to the whole thing - everything in this narrative is perfectly intentional, no matter how weird it might seem, and the ending will make you look at the whole thing in a new light.

Some Comics by Stephen Collins

I was drawn to this collection of single strips after reading Collins' brilliantly absurd

The Gigantic Beard That Was Evil. Unlike the aforementioned graphic novel, these single-page comics are much more comedy-oriented. I appreciated Collins' twisted sense of humour though and eagerly await whatever he does next!

Transmetropolitan by Warren Ellis

I'm about 6 or so volumes into this '90s cyberpunk series that, sadly, still feels blisteringly relevant in its satirical subversion of politics, society, and all things 'modern'. The protagonist, Spider Jerusalem, is one of the great non-superpowered anti-heroes of comics, and his invective-laden rants against the grimy futuristic dystopia he lives in are sharp enough to cut steel.

Comfort Food by Ellen Van Neervan

I grabbed Van Neervan's poetry volume after all the controversy that came out of her poem Mango being included in last year's HSC. Her work is sparse, thoughtful, intense, sensory, personal... I really enjoyed the wide range of verse and all I'll say in regards to the controversy is that it was unfounded, the Mango poem did its job in provoking such a diversity in responses. I hope Van Neervan has many more volumes of poetry to come.

Tranny by Laura Jane Grace

I'm a huge Against Me! fan, even if I do actually prefer the more polished and anthemic later stuff over their raw, folk-punk beginnings. In this brutally honest memoir, Laura Jane Grace combines her diary entries with a more straightforward narrative to describe her journey of discovery in relation to identity and gender. There aren't many transsexual music icons with as high a profile as Grace, which makes this autobiography a must-read for both punk-rock fans and those interested in gender politics and LGBT issues. It helps that Grace holds nothing back when discussing her family, friends, bandmates, music, etc., and it makes for a very entertaining and visceral read.

Dracula by Bram Stoker

I read this in preparation for teaching Year 11 Extension English 1 this year. I'd never read it before so I wasn't sure how it would go, but I actually liked it a lot. I'm coming around to accepting the disjointed nature of a lot of Victorian-era novels (it was always something I struggled a lot with in my younger days), and the opening five chapters of Dracula are probably my favourite part of Stoker's seminal vampire tale. I have no doubt that this because they're the most representative of how people commonly think of the Count and his predatory behaviour. The rest of the novel has elements worth reading too but, as I mentioned, it can feel disjointed at times. The biggest point of interest for me was how unromanticised Stoker's portrayal of Count Dracula is - not at all like the many iterations of vampires we've seen since.

The Analects by Confucius

I came across a statistic somewhere that claimed Confucius's Analects is the most read text of all time. I'm not sure if it's true or not but - considering China's long history, population, and influence on the world - it sounds legit, and that's why I thought I should read it. As a work of philosophy, I found it best digested over a few months, a couple of quotes at a time. As a 2500 year old text the context sometimes made it a little difficult to translate some parts (even when written in English), but I still found many quotes to be applicable to the modern day. I guess there's a reason why the wisdom of Confucius endures.

Dark Emu by Bruce Pascoe

This groundbreaking history book couldn't be more relevant to Australian society at this point in time. Pascoe has done something truly astonishing in bringing together extensive research, documentation, testimony, and first-hand experience to reconstruct Australia's pre-European past and thus deconstruct a lot of the myths surrounding what Aboriginal society looked like before Captain Cook's arrival. Pascoe not only makes an undeniable case for the idea of an Aboriginal 'civilisation', he also outlines the racist ideologies and methods that led to the erasure of this civilisation from white consciousness in the years since settlement. I found it both fascinating and enraging.

Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders

When I hear the words 'experimental novel' I tend to think I'll probably need to read it with a highlighter and a notepad, but Saunders' genre-defying historical fantasy bucks the trend and manages to be remarkably entertaining and heartfelt despite its structural idiosyncrasies. Told from the point of view of a collection of spirits 'stuck' between our world and the next, Lincoln in the Bardo mixes primary historical sources with outlandish speculation to capture the voices of America's 19th century. Easily worth the many awards it's won.

Rocannon's World by Ursula Le Guin

Le Guin's early science fiction novel is often overlooked in favour of her Earthsea Quartet or later sci-fi classics such as The Dispossessed and The Left Hand of Darkness. What makes Rocannon's World noteworthy is that it's the first entry in the 'Hainish Cycle' - eight science fiction novels (including the two mentioned above) that take place in the same fictional timeline/universe. Rocannon's World is a fairly brief concept-based novel that takes an anthropological look at human descendants living on an alien world, and uses some conceits related to the time distortions/differences that would arise in our theoretical exploration of space in the future. It's a neat sci-fi narrative but, as always, what makes Le Guin's work stand out is her knack for exploring the genre through a more post-modern perspective without leaving the reader behind.

Ready Player One by Ernest Cline

I wanted to see what all the hype was about and I think I'm lucky that I read this before I even realised it was becoming a film because the aggressively intertextual marketing campaign for Spielberg's movie would have turned me off altogether. Ready Player One isn't going to amaze any fans of award-winning literature nor will it prove intellectually stimulating to those who are normally attracted to sci-fi. What it does have going for it is a fun, geek-culture-heavy adventure that's easy to read and hard to put down. I enjoyed it, for the most part.

A Contract With God by Will Eisner

The name 'Eisner' has become synonymous with the graphic novel canon owing to this ground-breaking collection of longer-form comics. Eisner's use of the comic strip medium to explore dark, adult concepts was instrumental in the form's continuing development from superhero/comedy mainstay to a storytelling method that could be used to serve literature in a deeper fashion. A Contract with God remains highly arresting in its exploration of pain, loss, and displaced Jewish identity, and I found myself unable to tear away from each of the four thematically-linked stories - fascinated as much by the evidently heartfelt personal context and Eisner's seamless combination of word and image.

The Death of Stalin by Fabien Nury

It's easy to see why British satirist Armando Iannucci chose this one-shot graphic novel as the basis for his recent film of the same name. Inventively Machiavellian and as poisonous as any fatal snake bite, The Death of Stalin presents the true story of the Russian despot's demise and the political fallout that followed. In most hands this could have been a dry piece of historical retelling, but Nury zeroes in on the awful, the unbelievable, the rage-inducing, and the downright ridiculous to portray the final days of a bloodthirsty tyrant and the serpentine beginnings of the Cold War.

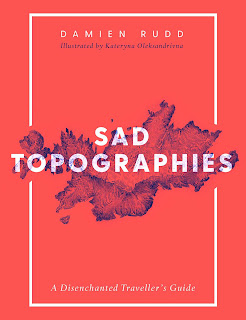

Sad Topographies by Damien Rudd

I'm a sucker for a quirky coffee table book. I saw this one in a Newtown bookstore and was immediately taken with its subject matter. Originating as an Instagram account, Rudd explores a series of depressingly named locations around the world with thoughtful essays on associated errata, etymological digressions, and miscellany. Places featured include Nothing, World's End, Isle of the Dead, Disappointment Island, and Port Famine.

Moonhead and the Music Machine

This graphic novel about the power of music, teenage misfitism, and what it's like to literally have a moon for a head is just the right mix of angst, comedy, and fantasy. I really enjoyed Joey Moonhead's journey towards acceptance and identity. His absurd friendships with other teenagers on the outskirts of the archetypal American high school are hilarious and visually arresting. A true gem.

The Finder Library Volume 1 by Carla Speed McNeil

Pulling together a diverse array of influences to mix together Indigenous narratives, comic styles related to Manga and online serials, and post-apocalyptic sci-fi, The Finder Library is a unique and genre-defying exercise in exotic world-building. McNeil ties together the narrative of Jaeger, a drifter with troubled origins, and the domestically-strained mixed-race family of Emma Lockhart and Brigham Grosvener. To give you an idea of the scope of this impressive series, McNeil's vision of the distant future explores the interrelation of racial identity and social standing, biological vs. culturally-constructed notions of gender, media consumption, and the impact of violence on the individual.

The Moon is a Harsh Mistress by Robert A. Heinlein

I've half-read a Heinlein before and couldn't finish it, so it was with some trepidation that I gave this one a shot. The Moon is a Harsh Mistress was enjoyable but also not without its issues. Told through the cynical eyes of one-armed computer technician Mannie, a 'loonie' (citizen of the Moon), The Moon is a Harsh Mistress relates the imagined revolution of Earth's lunar colony - paralleling the Bolshevism of 1920s Russia, nightmare scenarios of over-population and diminishing resources, and the 'free love' movement of the 1960s. The protagonist Mannie is thankfully the least annoying character in the novel, however, there is also a lot of political subplotting that doesn't really go anywhere quick enough, and the supporting characters veer between completely forgettable and incredibly irritating. That said, Heinlein's depiction of a lunar colony has some fairly interesting

dimensions, and I enjoyed the way it plays into the counter-culture of Heinlein's era. Notable for its invention of the phrase 'There's no such thing as a free lunch!"