|

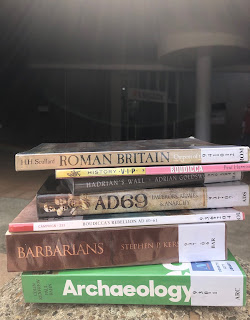

| Thanks Penrith Library! |

I thought I'd share with you today one of my current methods for researching and writing History curriculum. There's no single way to program, of course, but I do know that if someone had outlined a few methodologies to me back in my university days then it might have made things a little easier. I've experimented with various ways of writing programs for teaching and I guess that 2020-21 was the moment where I finally became happy with an approach to researching for the subject of History. So I thought I'd share it!

There were a few contributing factors that helped me arrive at the method I now use...

- In 2019 I was commissioned to write some chapters for the Cambridge History Transformed series. In order to feel comfortable in providing a baseline from which other teachers could work, I knew that I would have to undertake a considerable amount of research.

- At my new school I was placed onto Ancient History, a subject I hadn't taught for at least 9 years. For all intents and purposes I'm basically teaching it for the first time so I needed to refresh my approach.

- I fortuitously attended some online PL conducted by the History Teachers' Association of NSW. This 'Introduction to Ancient History' module was run by Dennis Mootz, who highlighted the use of Excel Spreadsheets as a powerful aggregation tool for historians to use.

- 1 = The Nature of Ancient History as it's the first module in the Preliminary course.

- 6 = The Treatment and Display of Human Remains as it's the 6th topic within the module.

- The four main dot points within this topic are then labelled A, B, C, D.

- Any sub-dot points within these are labelled with a further number, EG. 1, 2, 3, 4.

- The condition of the human remains and how they were preserved, discovered and/or removed from where they were found 1-6-A

- The methods and results of scientific analysis (dating of finds and forensic techniques) and modern preservation of the remains 1-6-B

- The significance of the human remains and other sources, for examples written, for an understanding of the life and times in which they lived, including: 1-6-C

- The social status of individuals 1-6-C1

- The beliefs and practices of the society 1-6-C2

- The health of ancient populations 1-6-C3

- The nature of the environment 1-6-C4

- The ethical issues relevant to the treatment, display and ownership of the remains, for example the use of invasive methods of scientific analysis 1-6-D

|

| Click to enlarge. |

- Information: My notes from the source in question. This can be a summary, or a quote, or a suggestion.

- Key Word: In something like this topic it's useful to be able to separate the entries geographically as the plan is to examine significant bodies from different parts of the world (EG. Bog Bodies from Europe, Mungo Man from Australia, etc.).

- Reference: This lets me know the source I've used. I keep another tab in the Excel spreadsheet running to collect together my sources as a proper bibliography.

- Page Number: So I can follow up in case I come back to the entry and realise I need more context, or need to check if I've quoted something correctly. After all, I don't want Keith Windschuttle to come after me (that's a joke for the History Extension teachers).

- Syllabus: The coding from Step 1. This becomes most important in the next step.

- Format: The type of source it's from. This can help me evaluate how I plan to use the information.

- Category: A categorising column additional to the Key Word column can be useful when it comes to sorting the document afterwards, in case there are different ways of ordering the information (EG. By culture/body rather than by geography).