Before looking at each of the texts in detail, here is a quick breakdown of representations:

- 3 novels, 1 suite of poetry, 1 drama text, and 1 film.

- 3 female composers, 3 male.

- 2 English composers, 2 Irish, 1 German, 1 Chinese-Canadian.

- Overview of eras: 1 text from the 1820s, 1 text from the 1850s, 1 from the 1920s, 1 from the 1950s, 1 from the 1960s-1970s, and 1 text from the 2010s.

Prose Fiction Options

North and South by Elizabeth Gaskell

What is it: Margaret Hale is the only daughter of a village pastor who has separated from the Church of England for ideological reasons. In order to make a fresh start, the Hale family moves north to Milton in the newly industrialised textiles region known as Darkshire. Margaret gets to know John Thornton, a wealthy nouveau riche mill owner who is struggling against worker strikes and unionisation, and the two begin an antagonistic relationship that soon grows into something built on mutual respect and admiration. Over the course of the next 18 months, the Hale family experiences great hardships and Margaret comes to intimately know the character of the north.

Scope for Study: North and South presents the prototypical Worlds of Upheaval that is later mirrored in Fritz Lang's Metropolis. Students will be able to deepen their understanding of Gaskell's serialised narrative through a close examination of its historical context, the Industrial Revolution that would quickly transform England into the most powerful empire of the 19th century. This approach will help to illuminate the various themes at play - the growing sense of class consciousness, debates around the unsustainability of capitalism alongside fair payment of the working class, the rise of new concepts such as wages and market forces and worker strikes, and the birth of a 'working class' identity.

NESA Annotations: There are no annotations for this text in any of the last three available NESA Annotations documents.

Verdict: It's a massive novel, and not necessarily all that fun a reading experience. At times I found North and South to be too self-consciously melodramatic for my tastes; evidently very much a product of its time (EG. The serialised format, the Victorian values that underpin it). I love the history/context of the Industrial Revolution and the concepts explored by Gaskell within the novel, however, North and South is such a chore to read that I can't imagine it going down well with the majority of Year 12 students.

Frankenstein by Mary Shelley

What is it: Frankenstein (yes, he's the scientist for which this novel is named - as most of us English teachers keep pedantically pointing out to our friends and families) is a mysterious frostbitten figure rescued by an Arctic explorer at the North Pole. After this framing device the reader begins to learn, through dual narratives, how Victor Frankenstein became grief-stricken in the wake of his mother's death. Burying himself at university in the rising disciplines of chemistry, biology, etc., Frankenstein develops a revolutionary way to give life to the flesh of the dead. He stitches together an eight-foot-tall abomination made from corpses and uses electricity to create 'The Creature', an intelligent child-like being who soon learns the cruelties of humanity through naive eyes.

Scope for Study: Students will need some grounding in regard to understanding the Gothic and Romantic genres, as well as Shelley's use of an epistolary structure, framing device, and the dual narratives of Frankenstein and the Creature in relating their parts of the tale. In terms of understanding context and thinking about Worlds of Upheaval, there's a lot to talk about, such as the development of an ideological antipathy between science and religion, the novel's claim to potentially being 'the first science fiction novel', and the text as an analogue for the Prometheus myth and all the historical connotation that carries. Attention can also be paid to Shelley's own personal context as the child of an anarchist father and a proto-feminist mother.

NESA Annotations: Annotations can be found in the 2015-2020 NESA document from when the text featured as part of Extension 1, Module B: Texts and Ways of Thinking. Areas of suggested focus include Shelley's use of characterisation and dialogue to elicit sympathy for the Creature, themes that arise from the novel's exploration of the tension between science and nature, and the role of the Romantic and Gothic genres in shaping the text and representing its concerns.

Verdict: I've read Frankenstein a few times but haven't taught it. I think - hope even! - that teaching it would be a rewarding experience as it's such a rich flashpoint in the history of literature. It's also, if one can offer such an opinion, of much better quality than the other 'big name' Gothic horror novels (I'm thinking specifically of the uneven Dracula and the undercooked Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde). If I were teaching Worlds of Upheaval I would probably start with Shelley's novel as the baseline text.

Do Not Say We Have Nothing by Madeleine Thien

What is it: A young Chinese-Canadian girl, Marie, gets to know Ai-Ming - a teenage girl and political refugee who has fled China after the Tiananmen Square Massacre in 1989 and now lives with Marie's family in Vancouver. The two bond over the 'Book of Records', a home-made text that contains the interwoven stories of their families from the days of China's tumultuous Cultural Revolution in the 1960s and 1970s. Several decades later, in the modern day, Marie becomes obsessed with tracking down Ai-Ming once again.

Scope for Study: The narrative of Do Not Say We Have Nothing is complex and multi-tiered, essentially covering 70 years of Chinese history and the stories of ten different characters who interact within it. In a way the novel can be boiled down to two separate but not dissimilar threads - one centering on the Cultural Revolution and the other on the Tiananmen Square incident, with both stories involving a search for dissidents hiding within the vast population of China. Any students studying this text will need assistance in the form of character maps to untangle the complex dynamics that take place across separate time zones, and historical timelines to help them understand China's recent past. This difficulty aside, the language is often nothing short of beautiful and Thien cleverly uses motifs of art and music to represent the subversion of a regime that could be both stifling and chaotic.

NESA Annotations: The most recent annotation document acknowledges the novel's focus on Chinese history and is quick to pull attention onto the "social, cultural and political upheaval" represented in Do Not Say We Have Nothing. Allusion and intertextuality are identified as key techniques used by the author, and the dense yet fractured structure is also highlighted as a reflection of the novel's themes.

Verdict: I'm not going to lie, I think this novel would be incredibly difficult to teach. I don't dispute its reputation as a work of significant artistic merit, however, I think it would be very easy for students to get lost in the unfamiliar history and the multitude of characters who weave in and out of the story across such a great expanse of time. And I say this as someone who has a fairly developed interest in China's history from 1950 to 1989 - it's an extremely difficult time period that has challenged and continues to challenge historians and casual readers alike. Approaching this book as a piece of serious literature (from an English standpoint) would need more time than what might normally be allocated for Extension English 1.

Poetry Options

Opened Ground by Seamus Heaney

- Digging

- The Strand at Lough Beg

- Casualty

- Funeral Rites

- Whatever You Say Say Nothing

- Triptych

What is it: Sampling a range of poetry from Heaney's output between 1966 and 1979, the suite selected from Opened Ground is unified by concerns relating to 'the Troubles', Northern Ireland's long period of unrest in the 20th century, and the relationship of the poet with his own context. The first poem, 'Digging', sees the poet and his pen contrasted with the traditions of the fathers beforehand; men who turned over the peat in search of potatoes, much as Heaney reflexively turns over the 'peat' of his mind by examining the role of the men in his family. The following poetry moves into looking at the Troubles, with 'Casualty' throwing stark light onto the violent juxtaposition between Irish domesticity and the impact of the unrest. 'Funeral Rites' delves further into this world torn apart, and 'Whatever You Say You Say Nothing' presents the silence and complication of the culture that grew from Northern Ireland's extended period of unrest.

Scope for Study: Students will need to have a strong understanding of Heaney's context, both in terms of the situation in Northern Ireland and the critical conversations around this poetry and its willingness to deal with the Troubles. Not all of the poetry included here was critically acclaimed upon its initial release, which opens up room for conversations around the controversy Heaney courted by daring to tackle a political dimension within his art. Students will also benefit from examining Heaney's use of naturalistic speech patterns, an array of sound and poetic devices, the use of sensory language and imagery, and the local colour of Irish culture, geography, and history.

NESA Annotations: The 2015-2020 Annotations feature some notes on Heaney's poetry in reference to its inclusion as part of a paired Advanced English study, where it was included alongside James Joyce's Dubliners. The focus here, in keeping with the paired study, is on the poetry's purpose in representing the lives and experiences of the Irish, and Heaney's use of traditional poetry forms alongside more modern approaches. It should be noted, however, that only two of the poems remain the same from this previous suite ('Digging' and 'The Strand at Lough Beg').

Verdict: Highly engaging and arresting, I think Heaney's poetry would work well as a stylistic and contextual counterpoint for any of the other Prescribed Texts in Worlds of Upheaval. Once the context is illuminated in enough detail by the teacher, students will have a lot to parse in their study of these poems as the language sits at just the right level - not too obscure, but also complex enough to reward repeated reading and careful analysis.

Drama Options

Waiting for Godot by Samuel Beckett

What is it: Vladimir and Estragon spend their time waiting by a tree for the arrival of an enigmatic individual named 'Godot'. While waiting they meet Pozzo and Lucky, two passers-by, and a boy who delivers a message that Godot won't be arriving on this day. The two protagonists return again the next day, in which the same events transpire.

Scope for Study: Famously referred to as a play where "nothing happens", playwright Samuel Beckett was famously reticent to provide anything in the way of an explanation for the strange narrative and characters, and rejected notions that posited metaphorical or allegorical levels of meaning. As far as students go, there will be, undoubtedly, discussions that arise from this. The power dynamics of people, demonstrated here without contextualisation or even the possibility of context, reveal certain absurdities that humans have created under the pretense that life has universal meaning. There are allusions to death, the Bible, and motifs of shoes and hats. What does it all mean? Is it about the absence or breakdown of meaning itself? Through Beckett's deliberate attempt to avoid a specific context, students are presented with a potentially fictional world of upheaval... or a metonym for every world of upheaval. There's a wealth of critical writing available on the play that will be helpful too.

NESA Annotations: There are no notes for Waiting for Godot in any of the available annotation documents from the last three syllabuses.

Verdict: Waiting for Godot is such a fascinating text and I think it provides a great canvas upon which students can test out their critical thinking skills. Vladimir and Estragon are almost like two shadows, humans consigned to immortality in a sort of purgatory world - going through the motions of trying to be human. In Act 2, the play itself seems to be resisting its own efforts to provide an internal context for what is happening; the characters are unable to even build their own 'world' in the absence of everything else. If it wasn't for Beckett's staunch rejection of the idea that the never-arriving Godot is really God, then I'd venture that this play presented a vision of Hell. Maybe it still does. Maybe it doesn't matter what Beckett says. Maybe this would be a great text to teach.

Film Options

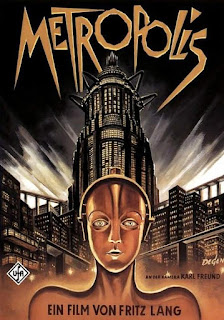

Metropolis, directed by Fritz Lang

What is it: Freder, the son of a powerful industrialist in the futuristic city of Metropolis, discovers class consciousness after his path crosses with the Madonna-like leader of the city's underground-dwelling proletariat. Meanwhile, the mad scientist Rotwang is enlisted by Freder's father to help infiltrate and sow dissent among the burgeoning revolutionary workers' movement. He does this by creating a robot impersonator, which unexpectedly becomes a symbol of wanton sexuality and hedonistic chaos after replacing the workers' leader Maria. Gradually, as Rotwang's own vengeful agenda subsumes his original mission, the opposing ideological forces that underpin the city begin to threaten this society's sense of order.

Scope for Study: Metropolis, in the tradition of most great science fiction, presents both a general view of a world in upheaval and reflects a specific context in which Germany and the rest of Europe were rapidly facing multiple crises. Fritz Lang (the left-leaning director) embraces the socialist ideals of class warfare in his depiction of workers who toil in drudgery and organise for revolution, whereas Thea von Harbou (the writer, who would later become a Nazi) could perhaps be seen as the influence behind the Art Deco grandeur of the city's architects. Coming at the more creative end of the silent film era, Metropolis does not fit the trope of the earliest static silent films, and is a visually dynamic experience that should hold up surprisingly well for modern students if context is suitably explained beforehand.

NESA Annotations: Notes for Metropolis can be found in the 2015-2020 document from when the film formed part of an intertextual study with Nineteen Eighty-Four for Module A of Advanced English. The annotations focus on Metropolis's function as a dystopian text that explores the impact of technology and totalitarianism. Note is also made of other contextual elements: the Weimer republic, German expressionism, the Art Deco and Modernist movements of art and architecture, the groundbreaking special effects utilised by Lang. Aside from a few cursory connections to Nineteen Eighty-Four the annotations are still fairly useful within the framework of the Worlds of Upheaval Elective.

Verdict: A fantastically-made film that's so ahead of its time that it's managed to stay relevant for nearly 100 years. As with most English Prescribed Texts, the mileage of this (in terms of appealing to students) will be dependent on the enthusiasm of the teacher. I would no doubt teach this text if I found myself teaching this particular elective as I find it to be so worthy of study; the shot composition, the way it reflects its context, the fascinating Biblical allusions that verge on the baroque, and - of course - the appallingly decadent robot Maria.